The central motif of Hubert Czerepok’ oeuvre are the connections between fiction and truth in historical accounts. It is not the facts themselves that interest the artist, but rather the ways in which they mutate and undergo formal and semantic transformations.

As his artistic interests developed over the years, Czerepok never restricted himself to one particular medium. For each subject, he chooses such means that will best reflect its nature. Hence, his work, apart from drawing and photography, encompasses video installation and installation with architectural structures.

For the video installation “Devil’s Island”, the artist visited a rocky islet off the coast of Kourou in French Guiana (famed for the penal colony to which many French political prisoners – including Alfred Dreyfus – were condemned). Between 1852 and 1951, the infamous “Île du Diable” was home to over 70,000 prisoners. Apparently, Czerepok must have been charmed by a peculiar mixture of facts and historical inconsistencies, which to some extent were instigated by the romantic vision of the island created by Henri Charrière in his classic memoir “Papillon” (“Butterfly”) – a semi-biographical and semi-fictitious account of a successful escape from the prison island.

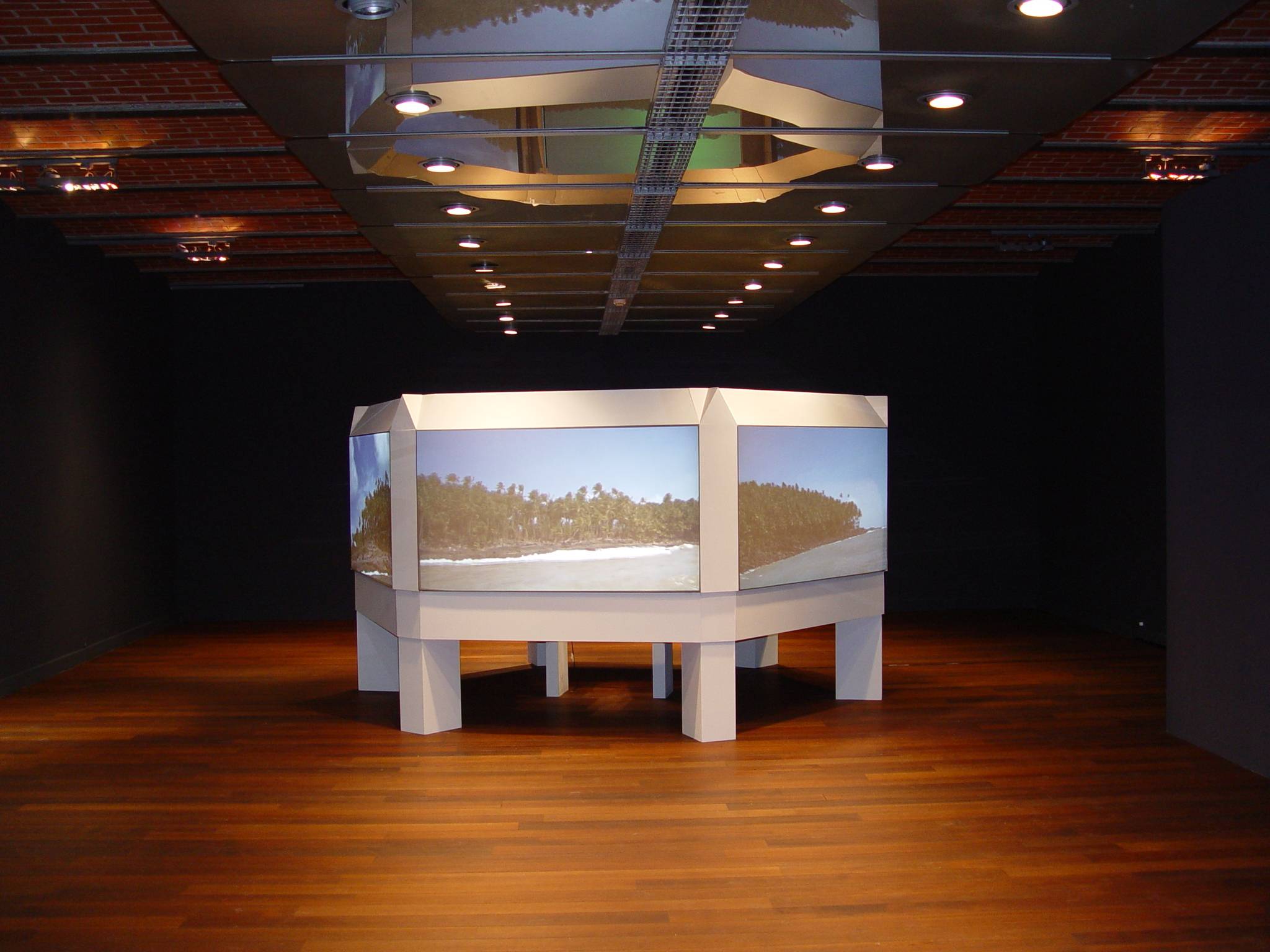

In the installation, images are projected onto a hexagonal sculpture referencing another form of disciplinary power: the Panopticon. Part of a circular prison building, the Panopticon allows full-time surveillance of prisoners without their knowing if they are being watched or not, the result being a sense of invisible omniscience. The artist uses this heavily symbolic and visually original construction as a framework on which he can cast beautiful images of tropical island landscapes. The landscapes that appear on the walls of the prison model open a totally new perspective, allowing us to see the outside from the inside. The artist offers us a multi- perspective visual experience. The island, once isolated and closed, opens up and expands in front of us on the hexagon walls. Its story is told anew.

The exhibition also features two series of drawings created in 2009: “Seances (after Disasters of War)”, which pay tribute to Goya’s “Disasters of War” engravings, and the latest cycle, which portrays the ruins of destroyed and abandoned churches. The black and white drawings on paper appear to have no particular background detail. The crude simplicity of black lines adds an overwhelming sense of purity to the compositions as they meet our eyes. Each of them is clear, devoid of any redundant visual content that could obstruct our analytical appraisal of the tragic scenes being depicted. Seeing the ruined churches, whose shapes are defined by black shades, we almost palpably feel the force of the static lines and the ever growing depressing silence. The other cycle, “Seances (after Disasters of War)” is a mass media-modeled vision of human cruelty, captured by the artist in a new critical form.

The exhibited works stimulated reflection not only on the notion of historical truth, but also on the circumstances that lead humanity to self-destruction. The new series depicting burnt churches had its premiere exhibition at Art Stations.

Since the beginning of the 1970s Anselm Kiefer has been drawing inspiration not only from the history of his birthplace, Germany, but also from the rich tradition of European mythology, which has turned out to be an endless source of creative inspiration for the artist.

Along with an interest in academic publications and a passion for astronomy, he has developed a fascination for shamanism. Since the 1990s, he has been studying the Kabala, treating it as a rich source of symbols and myths about the beginning of the world, which offer immense interpretative potential. In Kiefer’s work, elements of religious and mythological iconography meet contemporary history. Next to Günter Grass, Anselm Kiefer is said to be a voice of contemporary German consciousness.

The painting presented at the exhibition is part of a highly regarded series inspired by the work of Paul Celan (1920-1970), a Romanian poet of Jewish origin. Stretching to the distant horizon, the landscape of an empty field covered with mud and snow instantly leads the viewer beyond the visual field. The layers of paint, one applied over another, evoke the sensation of the earth’s structure. However, what makes the strongest impression is the three-dimensional appearance of the painting due to the structure of its foreground. This is where the artist has attached life-size chairs, a pile of tree branches, and a heap of human hair.

Anselm Kiefer sees “Das Haar” as a medium which can transform the viewer of this work into a witness of war – the war that echoes all around in the sprawling empty landscape and the dark, quiet sky. The three chairs are attached to the face of the painting: one with tree branches, one with a pile of hair, and in between the two – one that is empty, as if symbolically waiting for the viewer. Inviting us to take a seat, the empty chair offers a position in the center of the picture and, at the same time, in the center of history. Sitting with one’s back to the visual field, one becomes integrated into it. The viewer therefore becomes an integral part of the landscape. His involvement goes beyond passive watching; he is an active witness who must cope with the perception of the Second World War and the inevitable issue of responsibility. In this way, “Das Haar” defines the relations between the artist and the observer, between the viewer and the past, in an innovative way.

Kiefer’s work carries many meanings, including references to the heavy burden of history, for which it has become one of the most widely recognized works of the artist born in 1945 in Germany – a country that was in a deep political, economic and moral crisis. The artist belongs to the generation that entered the post-war context experiencing both amnesia and a sense of guilt. Thus, we can interpret the empty chair in his work not only as a sign of invitation but also as a serious challenge requiring moral maturity and psychological courage from all those who are about to face it. It calls us to enter this landscape of thoughts, gloomy as it is painted, and invites us to reflect on the faith of those who, though innocent, had to die a tragic death. Loneliness, sadness and historical responsibility are reflected not only in the physical form of this difficult work – they also claim the symbolic terrain of thought, a land which has its place somewhere in a timeless space created by the artist.

Anselm Kiefer’s work “Das Haar”, 2006, a painting from Grażyna Kulczyk Collection, was presented for the first time to a wider audience in Poland. While engaging in reflection on the work and its subject, our thoughts were with the victims of Auschwitz-Birkenau Death Camp in the 65th anniversary of its liberation.